resilience

My mother sat on the edge of the bed observing her eight-year-old crying and writhing in pain following the family's annual summer seafood fest. As she paused to assess the level of my distress and how best to respond, I was imagining an ambulance ride to the hospital, where loving doctors and nurses would greet me with open arms and instantly make everything all better. No doubt, my salvation fantasy stemmed from a series of books I happened to be reading at the time, titled: "Cherry Ames, Student Nurse".

Quietly, attentively, mother continued her vigil at my side. After a time, she suddenly stood up and pronounced with the utmost confidence, "You will feel better in the morning," and left the room, closing the door behind her. I wailed at her abandonment of me while I lay dying. Cherry Ames would never have done such a thing.

When I related my childhood deathbed experience to a group of students, it elicited an audible and collective gasp, accompanied by expressions of shock, pity, and disbelief. Surprised by the reaction, I quickly assured everyone that while it appeared my mother's behaviour was cruel, in reality she had given me one of the many priceless gifts I was to receive growing up under her wing; the gift of resilience. And sure enough, just as my mother predicted... I felt better in the morning.

To be resilient is to be capable of withstanding shock without being permanently altered; it is to be elastic, and buoyant; to possess the ability to recover, to bounce back, to cope after being squeezed, compressed, crushed. My parents were the first to teach me how to bounce when things failed to live up to my desires and expectations. Growing up sandwiched between four brothers also helped, immensely. And once I graduated into adulthood, life stepped in where the family left off.

Fast-forward twenty years or so, and I was studying massage therapy in Germany, with an eighty-something-year old Lilliputian Frau that I was thoroughly intimidated by. During the first practicum where our skills were being assessed, the Frau made a beeline for me as I worked on another student. Standing on the other side of the table, she picked my hand up off of the "patient" and slapped it, exclaiming: "Your hands are like vood!" Mortified, I left the room and made my way to the bathroom, where I proceeded to bawl my eyes out in one of the stalls.

Eventually, once I had sort of recovered myself, I opened the stall door to find the Frau standing but a few inches away from me, arms akimbo, a fierce look in her eyes, and shocks of white hair that had let loose from her coiffure as if she had just exited a wind tunnel.

I immediately unleashed a torrent of reasons to justify my extreme upset: "I am exhausted... I don't feel well... I have jet lag...my brother is in Iraq"...etc., etc. Eventually, I ran out of reasons for my mental and emotional instability, and noticed the Frau staring at me like I was a freak of nature. After a timeless pause, she raised one arm up, her elbow bent, fist clenched, and said: "Yes. Annnd...you must be strong in zeeee vorld!" And with that, once again, as destiny would have it, I was shocked out of my poor-me reverie.

Experiential medicine (the best kind when taken as directed), has a way of giving us what we need, when we need it. It comes in the form of cues we receive from life’s vicissitudes; messages meant to wake us up from the deep hypnotic distractions of the material world.

Cues always begin on a subtle level. Subtle messages unheeded get progressively louder and denser, manifesting eventually as shocks meant to jolt us (ideally) out of our fixed prejudices, and back into present moment Reality. I like to refer to these shocks as the "frying pan upside the head" phenomenon, which I happen to have a lot of experience with. Life is endlessly creative in the ways it continually attempts to wake us up to the Truth of Being.

Knowledge, understanding, and their offspring resiliency, are the byproducts of present moment contact (contact without prejudice) with life experiences and events; even and especially the ones that cause suffering, our own as well as that of others.

When my son’s best friend finally regained consciousness after falling four stories down an elevator shaft, his first words were: “Hopefully I will come out of this with lots of new and good ideas.” Just out of high school, it took his body two years to heal from the trauma of the fall, multiple surgeries, and all the therapies he endured. Although I saw him frequently during his recovery, I never once heard him complain. It is powerful beyond measure to bear witness to that kind of resilience.

I used to think Buddha was a having a bad day when he said: "life is suffering". What did he mean exactly? Perhaps like many wise ones who have come before, he was giving us a heads-up about what to expect, and guidance in how to live life as a spirit stuffed into a physical (material) body, in a material world.

Imagine squeezing yourself into a pair of shoes two sizes too small, and then spending seventy or eighty years traversing the peaks and valleys of a strange land. Chances are, you will experience a few blisters along the way - there will be some suffering. Can suffering be avoided? No. Sorry. Not until the shoes come off.

If Buddha and the others are right when they warn that life is suffering, then to believe that our lives are always supposed to be beautiful, comfortable, and convenient would be...delusional. Deluded, we would be thoroughly unprepared, and ill-equipped to manage ourselves, and all experiences that fall outside the narrow parameters of our beliefs, desires, and expectations in both the material and spiritual worlds.

A natural and free balm for life's blisters, resilience is a powerful medicine with a long track record in safety and efficacy. Resilience works to relieve suffering individually, and collectively by reorienting the creative power of mind away from the meaningless, and back to the meaningful. There are no known harmful side effects.

Sadhana:

Resiliency is natural to a mind-body system in balance (health). If you find yourself deflated, to build your ability to bounce back, first look to fortifying the basics of good health.

Next, the nervous system. The nervous system is divided into two parts, the parasympathetic (rest and digest, standby) mode, and the sympathetic (high alert, fight-or-flight) mode. A proper functioning nervous system is astoundingly resilient, as it flawlessly switches between the two modes as needed.

When a threat, real or imagined, is encountered, the nervous system flips into high alert mode. It is not at all uncommon to get "stuck" in high alert when we experience prolonged periods of illness, stress, or when we have a strong imagination that likes to make mountains out of molehills.

A nervous system on high alert is designed to be used for emergency purposes only. Constantly running on high alert when there is no real or immediate threat wears us out physically, mentally, and emotionally. Being in a continuous high alert state (prolonged stress) we are unable to digest and assimilate our food, our thoughts, emotions, and experiences.

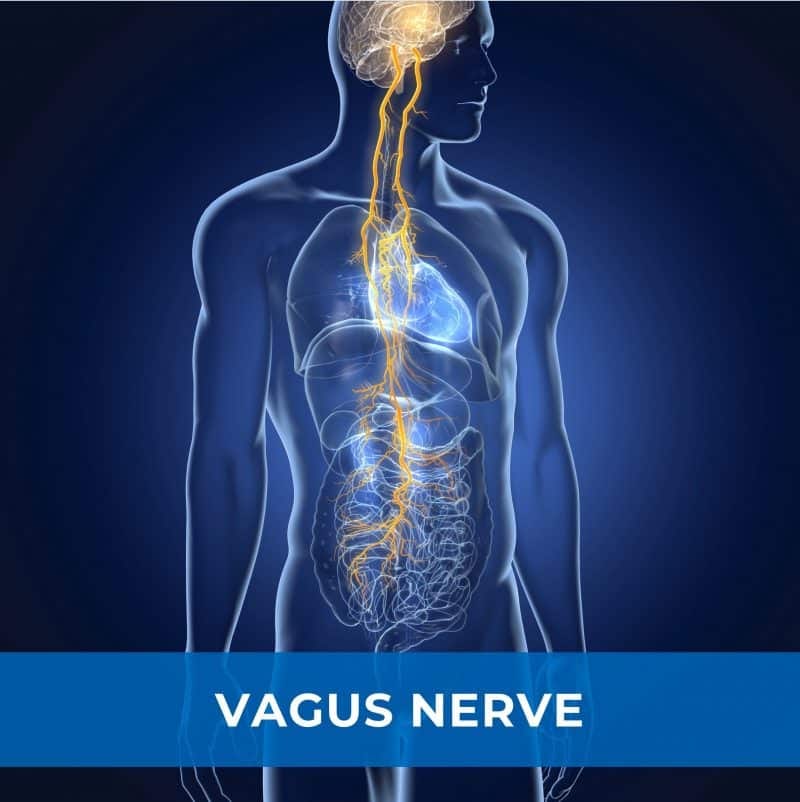

The vagus nerve is a large nerve that runs from the brain, through the right and left side of the torso, to the large intestine. It plays a key role in managing body functions like heart rate, blood pressure, digestion, respiration, and immune system response. The vagus nerve is also a physical switch that stimulates the nervous system into high alert mode, or into standby mode, depending on what the real or imagined situation calls for.

You can stimulate the vagus nerve to switch off high alert and switch on standby mode with a simple breath awareness exercise. This is best done first thing in the morning, and can be repeated throughout the day as needed. You will realize a deeper and longer lasting effect if you practice it on a regular basis; once a day, the same time of day is best. With consistent practice, the function of the nervous system will normalize, and you will feel yourself more relaxed, alert, and resilient.

The rest and digest breath:

Sit comfortably, with the spine long, chest lifted.

Take a few easy deep breaths.

Feel the body relaxed.

Feel your whole self relaxed.

Keeping body relaxed, exhale the breath all the way.

Now, inhale to a slow count of 5. Slow. Imagine you are inhaling deep into the lower belly

Pause

Exhale to a slow count of 5. Slow.

Pause

Repeat the sequence five times, total.

At the end of round five, once you have exhaled the breath, let go of any conscious control of the breath and sit quietly for a few moments.

Notice how you feel.

Welcome home.

When ready, open the eyes slowly.

PS: Research as depicted in the 2024 documentary “Giants Rising,” tells us that just looking at a redwood tree has beneficial effects on the nervous system. If you don’t have a redwood nearby, any large tree will most likely have a similar effect. Test it out and see.